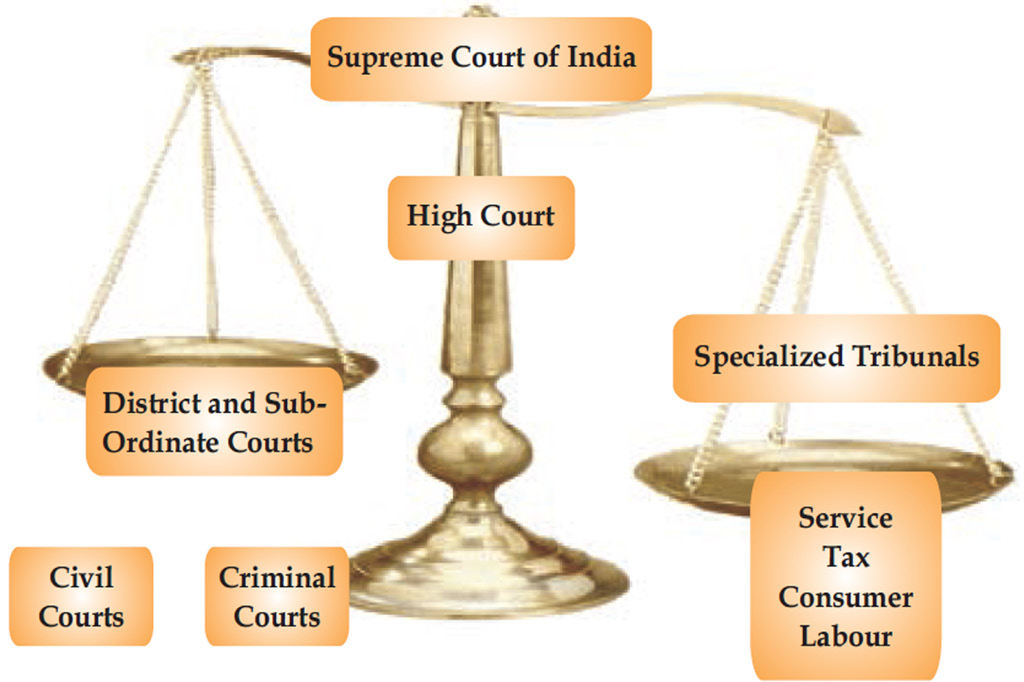

Structure and Hierarchy of Courts in India

The Constitution of India lays out the framework of the Indian judicial system. India has adopted a federal system of government which distributes the law enacting power between the Centre and the States. Yet the Constitution establishes a single integrated system of judiciary comprising of courts to administer both Central and State laws. The Supreme Court located in New Delhi is the apex court of India. It is followed by various High Courts at the state level which function for one or more number of states. The High Courts are followed by district and subordinate courts which are known as the lower courts in India. To supplement the functioning of the courts, there exist specialised tribunals to adjudicate sector specific claims such as labour, consumer, service matter disputes.

Supreme Court of India

The Supreme Court of India came into being on 28 January,1950.It replaced both the Federal Court of India and the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council which were at the apex of the Indian court system, under the colonial era. The Constitution of India as it stood in 1950 envisaged a Supreme Court with a Chief Justice and 7 Judges. The Parliament was granted the power to increase the number of judges in thecoming years. At present, the total strength of the SupremeCourt is 34 judges including the Chief Justice of India. Agroup of judges sitting together on a legal matter in theCourt constitutes a bench. A division bench comprises oftwo or three judges. A constitutional bench comprises offive or more judges and may even extend to thirteen judges.

High Courts

India consists of 25 High Courts at the state and union territory level. Each High Court has jurisdiction over a state, a union territory or a group of states and union territories. Below, the High Courts exists a hierarchy of lower courts functioning as civil courts and criminal courts as well as the specialised tribunals. The Madras High Court (1862) in Chennai, Bombay High Court (1862) in Mumbai, Calcutta High Court (1862) in Kolkata and the Allahabad High Court (1866) in Allahabad are the first four High Courts in India.

District and Sub-ordinate Courts

The courts that function below the High Courts are popularly known as the lower courts. They consist of district and subordinate courts. Each state is divided into judicial districts presided over by a ‘District and Sessions Judge’. The judge is known as a ‘District Judge’ when she/he presides over a civil case and a ‘Sessions Judge’ when he presides over a criminal case. The district judge is also called a ‘Metropolitan Sessions Judge’ when she/he is presiding over a district court in a city which is designated as a metropolitan area by the State government. District judges may be working with Additional District judges, depending upon the judicial workload.

The district judge is the highest judicial authority below a High Court judge. The District Court also holds appellate jurisdiction and supervision over all sub-ordinate Courts below it. On the Civil side, the sub-ordinate Courts below the District Court include (in ascending order) – Junior Civil Judge Court, Principal Junior Civil Judge Court, Senior Civil Judge Courts (also called sub-Courts). Sub-ordinate Courts on Criminal side (in ascending order) include: Second Class Judicial Magistrates Court, First Class Judicial Magistrate Court and Chief Judicial Magistrate Court. Apart from the sub-ordinate courts, Munsiff Courts also form a part of this hierarchy. They are the lowest in terms of handling matters of civil nature and function below the subordinate courts. Their pecuniary limits, meaning the court’s ability to hear matters upto a particular claim for money, are notified by respective State governments.

Tribunals

Apart from these judicial bodies, Indian judiciary is also characterised by numerous semi-judicial bodies involved in dispute resolution. These bodies function as semi or quasijudicial bodies because they may consist of administrative officers or judges without a legal background. Yet they function in their judicial capacity and hear relevant legal matters and settle claims between the parties.

Tribunals have been constituted under specific constitutional mandate enshrined in the Constitution of India or through legal enactments, e.g., a law passed by the legislature. Their creation aims at increasing efficiency in resolving disputes and reducing the burden on courts. Examples of some of these tribunals include: Central Administrative Tribunal (CAT) for resolving the grievances and disputes of central government employees, and State Administrative Tribunals (SAT) for state government employees; Telecom Dispute Settlement Appellate Tribunal (TDSAT) for resolving disputes in the telecom sector in India; and the National Green Tribunal (NGT) for disputes involving environmental issues. Some of these tribunals function with regulators. Regulators are specialised government agencies that oversee the law and order compliance in the relevant government sectors. For example, one of the tribunals TDSAT functions alongside the regulator, TRAI (Telecom Regulatory Authority of India) in formulating laws and policy for resolving telecom disputes in India. Therefore these tribunals complement and supplement the role of courts in maintaining law and justice in the society.